Emissions Accounting in the Climate Crisis

Why now it's more important than ever

Why now it's more important than ever

15 min read

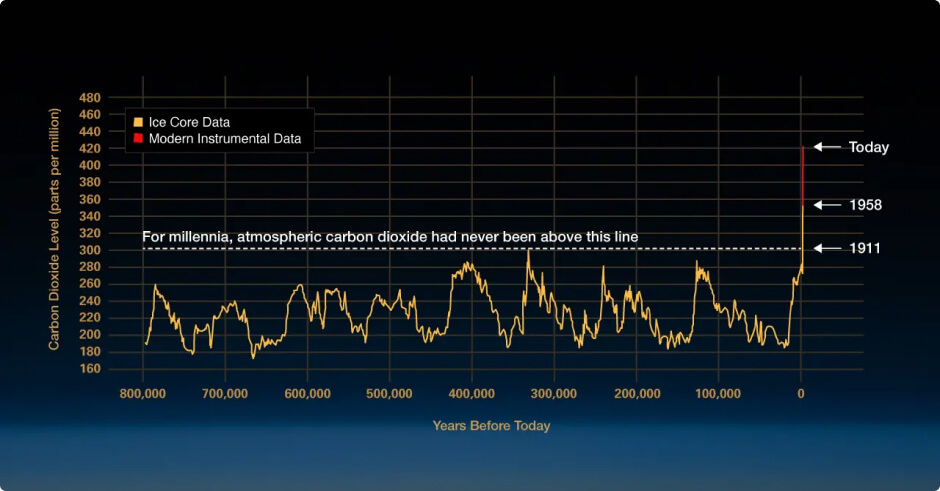

Although great uncertainty still surrounds the climate issue and its potential impacts, the belief that the climate is undergoing major changes due to human activities has reached very broad levels of consensus among scientists. Today, one of the most authoritative institutions in the field of climate change is certainly the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Founded in 1998 by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), it has the noble purpose of providing politicians around the world with an overview of the latest findings on climate change and its potential socioeconomic impacts through a review and synthesis of the scientific literature. The same organization also adds recommendations and suggestions about the policies to be adopted for mitigation and adaptation to this phenomenon.

According to the IPCC:

"Scientific evidence for warming of the climate system is unequivocal”

According to the IPCC:

"It is very likely that heat waves will occur more often and last longer, and that extreme precipitation events will become more intense and frequent in many regions. The ocean will continue to warm and acidify, and global mean sea level to rise“

The international community's response to the climate emergency was undoubtedly late but has reached a significant success in recent years. The Paris Agreement, signed in late 2015 during the 21st COP (Conference of the Parties), represents the most important international agreement regarding greenhouse gas emissions.

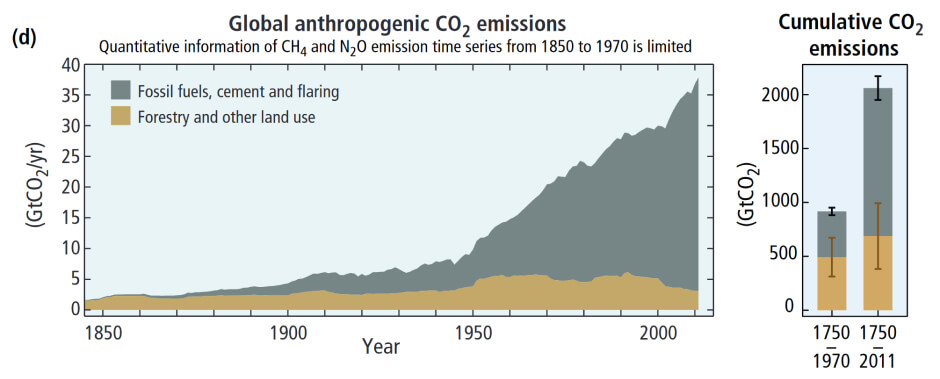

In fact, although for decades there have been several attempts to find agreements at an international level between the major emitters, most of the conferences have turned out to be utter failures. Starting from the Rio de Janeiro conference in 1992, up to the more well-known Kyoto Protocol in 1997, these diplomatic efforts had the merit of drawing attention to the problem but have never produced tangible results, and emissions continued to grow uninterruptedly. Even in more recent years, as it happened in Copenhagen in 2009, the world's expectations have been consistently disappointed due to agreements between the main emitters, who have banded together to counter the efforts (particularly European ones) aimed at building a set of objectives capable of leading to a gradual reduction of emissions.

The Paris Agreement is not only the last major climate agreement in chronological order, but it represents the very first universal and legally binding agreement on climate change. In Paris, governments representing nearly 200 countries, finally agreed on the need to keep the temperature increase "well below" two degrees centigrade and to do everything possible to "limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C“ compared to the pre-industrial era. The text also sets the ambitious objective of a completely decarbonized economy starting from 2050. The fact that the agreement is legally binding is, however, mitigated by the reliance placed on "Intended Nationally Determined Contributions“, voluntary contributions determined by individual Nations, through which emission reduction takes place. Furthermore, although each adhering country is obliged to set a reduction target, there are no sanctions in case of non-compliance.

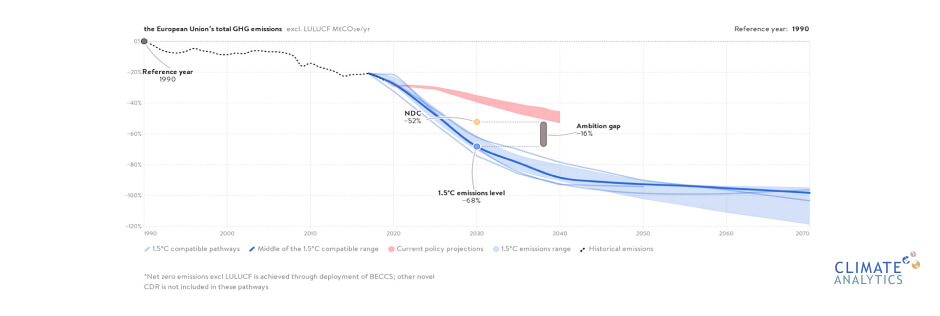

In the post-Paris agreement world, the European Union has clearly emerged as the “Climate Leader”. This, on top of a generally growing economy and a strong environmental consciousness, has been undoubtedly facilitated by a rapidly changing regulatory framework that has defined emissions reduction as one of its priorities.

The impetus for this regulatory evolution can surely be attributed to the European Commission led by Ursula Von Der Leyen who, in 2019, proposed an ambitious 26-page document called "The European Green Deal".

“The European Green Deal is […] is a new growth strategy that aims to transform the EU into a fair and prosperous society, with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy where there are no net emissions of greenhouse gases in 2050 and where economic growth is decoupled from resource use”

These 26 pages have taken on an epochal importance for the European Union, as they have guided its economic policies and given an unprecedented acceleration towards decarbonization. The afore mentioned document has brought the EU to approve several far-reaching reforms that are transforming corporate Europe, such as the European Taxonomy, the Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (SFDR) or the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD).

Over the past few years, calculating and reporting an organization’s emissions has significantly grown in importance. Governments, banks and particularly large corporations have increasingly started to report on their climate altering emissions, both to meet regulatory requirements and to demonstrate their efforts to the consumers.

A wide body of scientific literature demonstrates that nowadays consumers are often willing to pay more for greener products and this has led to corporations competing against each other to prove themselves as the most sustainable alternative. Emissions calculation and reporting, however, is quickly transforming from a great source of competitive advantage (see for example «Sustainability and Competitive Advantage: A Case of Patagonia's Sustainability-Driven Innovation and Shared Value” Rattalino 2019) to a minimum strategical and regulatory requirement. It is becoming obvious, in fact, that the companies that do not properly communicate their sustainability efforts will suffer a loss of competitiveness in an always greener market, steered by the growing environmental consciousness of younger generations and by more restrictive policies.

On January 5th, 2023, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) entered into force in the EU, significantly broadening the scope of the entities that will have to report, starting from the FY 2025, on several ESG topics, including CO₂ emissions. The directive also aims at aligning the many existing reporting standards under one «European Sustainability Reporting Standard» and mandates a limited assurance from a statutory auditor, therefore elevating the importance of the sustainability report to that of the balance sheet.

In such context, it is therefore increasingly clear that calculating emissions, disclosing them and establishing efficient reduction strategies is nowadays essential to ensure competitiveness in European and international markets.

Different economies present different degrees of development, different climates, different policies and different energy mixes. Consequently, emission intensities vary widely. Although all companies have in emission reduction initiatives both an imperative and a great opportunity, organizations located in different countries may have to follow different paths to reach carbon neutrality.

Over the past few years, calculating and reporting an organization’s emissions has significantly grown in importance. Governments, banks and particularly large corporations have increasingly started to report on their climate altering emissions, both to meet regulatory requirements and to demonstrate their efforts to the consumers.

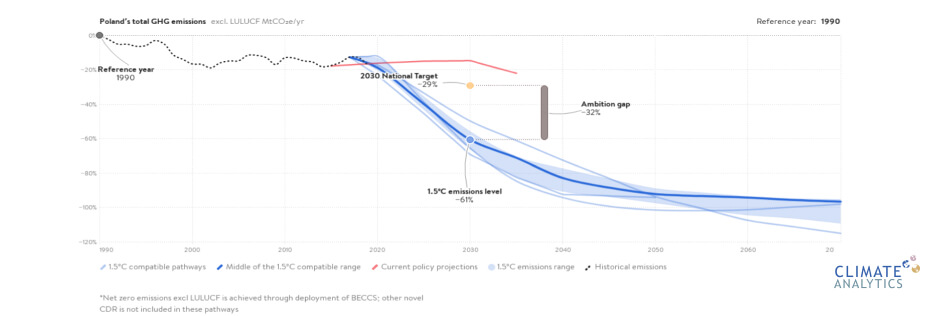

However, to face such a successful industrialization, the country has broadly relied on fossil fuels. Poland’s energy mix today is highly based on coal (~70%) but this fossil fuel would need to be phased out by 2029 for the country to be in line with 1.5°C pathways. Moreover, high car ownership and slow electrification have contributed to the booming emissions of the transport sector.

To counter the increasing industrial emissions, Polish factories should first and foremost focus on scaling up electrification. This will ensure the maximization of benefits once nuclear power plants will be active in the country.

At the same time, corporations can play a key role in driving down emissions by investing heavily in on-site production of clean energy through solar panels and in energy saving initiatives (e.g LED lights, heat recovery and insulation). On top of reducing climate altering emissions, this would also represent a fundamental hedging strategy in case of further spikes in energy prices, helping to increase energy security in times of geopolitical tensions.

Polish companies, compared to their European counterparties, often display a lower focus on sustainability. This is coherent with the lower environmental awareness displayed by former socialist countries. This gap represents a unique opportunity for Polish companies.

As previously mentioned, achieving high environmental performance is an undeniable source of competitive advantage. Investing today in building a climate strategy (i.e., in the calculation, reporting and reduction of emissions) would be a very profitable investment in an economy where only a minority of actors can boast about being sustainable. Starting early to build a reputation of a "sustainable company" will ensure greater loyalty and profitability once the environmental awareness of Polish citizens will catch up with the rest of Europe.

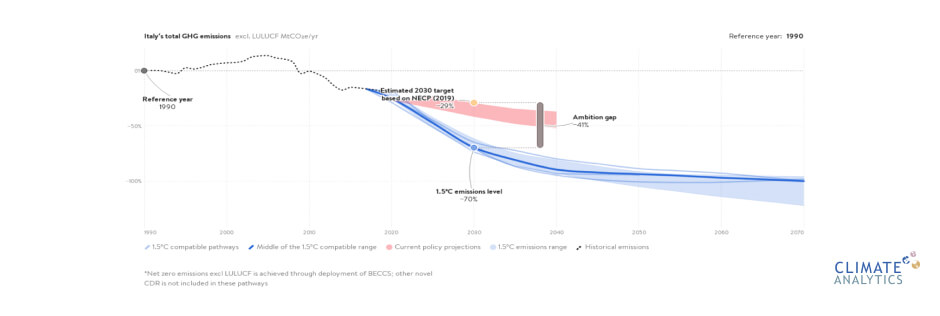

Being the third largest European economy and the third most populated country in the Union, reducing Italy’s emissions is key to reaching the Green Deal’s targets. The country’ emissions, after booming between the 1960s and the 1990s have peaked in 2004 and have strongly decreased ever after. This is mainly due to periods of economic turmoil and industrial relocations outside the country.

Despite all of this, Italy displays a strong gap compared to 1.5° compatible pathways. Transport represents the highest emitting sector as electric vehicles are not yet mainstream and the country has one of the highest numbers of vehicles per capita in the EU (source ACEA, see next page). Moreover, Italy’s energy mix heavily relies on natural gas and, for 14%, on the more polluting oil and coal. To be compatible with a 1.5° scenario, the country would need to increase its renewable energy production to reach a share of 82-87% by 2030, compared to around 35-40% in 2019.

Industrial emissions in Italy have decreased by 35% between 2003 to 2019, though this is largely due to an overall decline in industrial activity. Within this sector, an important role is played by the production of iron and steel, which contributed roughly 20% of total industrial CO₂ emissions in 2019.

For these emission-intensive, “hard to abate” activities, certain companies have already started to invest in green hydrogen, but higher industry involvement is needed. To be compatible with a 1.5° scenario, businesses would also need to boost electrification and increase production of clean energy.

Thanks to the high solar potential, corporations can reduce their emissions by investing in on-site solar energy production, which also helps to mitigate the high energy costs. Finally, given that transport represents the highest emitting sector, Italian businesses should opt for the electrification of their car fleets where possible or incentivize the use of bicycles/car sharing for their employees.

Spain’s annual CO₂ emissions grew exponentially between 1960 and 2005, increasing from 48 to 370 million tons. In recent years, figures have sharply decreased to reach 233 million tons in 2021. While a part of such decrease is due to the 2007 financial crisis, Spain has certainly put in place important reforms that have supported an impressive growth of renewable energy generation.

To hit net zero by 2050, the country’s efforts should be focused on its transport sector, which accounts for roughly half of the country’s emissions. On top of the investments needed to achieve a complete electrification of cars and motorcycles by mid of the century, biofuels and synfuels would have to be used to reduce the domestic aviation’s carbon footprint.

Industrial emissions in Spain could be greatly reduced thanks to the deployment of carbon capture and storage projects and the use of green hydrogen. The latter should greatly benefit from the country’s leadership in the field of renewable energy, a field that still offers massive opportunities for growth thanks to the highest solar potential in Europe (source: solar atlas, next page).

This makes it convenient for businesses of every size to locally generate clean energy or to enter renewable power purchase agreements. Additionally, companies should keep investing in energy efficiency solutions and incentivize employees to avoid using their cars to reach the place of work.

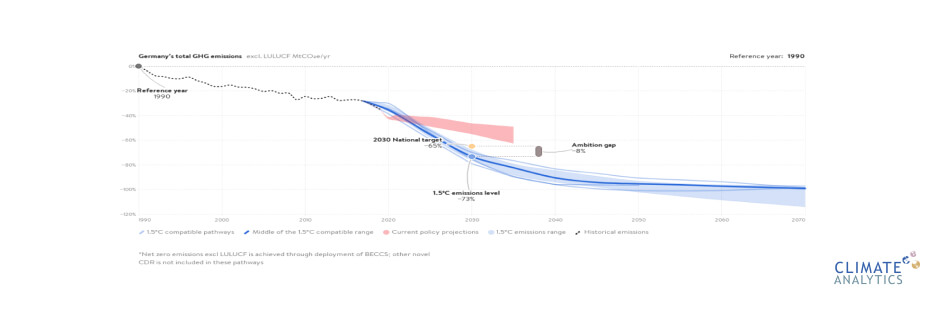

After peaking in 1979, the largest European economy’s emissions have decreased nearly 40% despite solid GDP growth. However, Germany’s recent decision to phase-out nuclear power has led to an increased energy production from coal and to increased emissions. Furthermore, the residential sector suffers from a low renovation rate and less efficient homes keep consuming major energy amounts.

The German industry has achieved important emissions reductions over the past few years but could highly benefit form the deployment of green hydrogen for the “hard to abate” emissions, such as those connected to the production of steel or cement.

Great emission savings could also come from a more circular economy. As stressed by the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research “The expansion of material recycling not only helps to save primary raw materials, but in most cases also leads to a significant reduction in energy consumption in production”.

However, the main drivers to decrease energy related emissions in the industry sector according to the 1.5°C compatible pathway are electrification and energy efficiency measures.

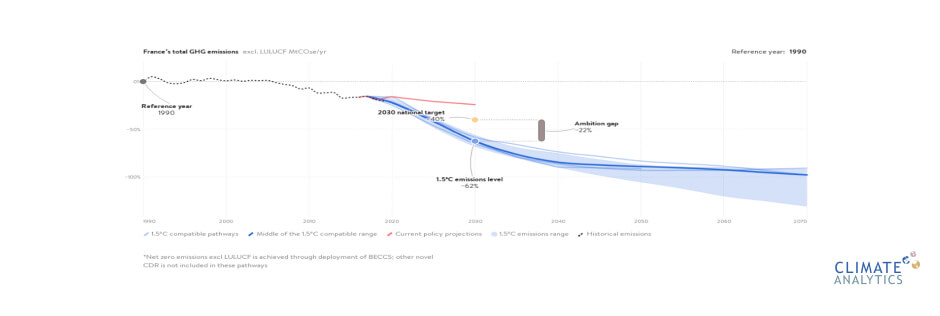

France’s emissions have decreased nearly 40% compared to the 538 million tons recorded in 1973 and, thanks to its numerous nuclear power plants, the country boasts very low CO₂ per capita emissions.

However, to be in line with 1.5°C pathways France would have to sharply increase the share of electricity in the transport sector, the biggest national emitter, and to encourage a modal shift.

Emissions from the industrial sector would need to be further reduced by 42-47% by 2030 to be in line with the Paris agreement. To achieve such goal, companies need to invest heavily in electrifying industrial processes and to boost renewable generation capacity to allow for a total phase out of fossil fuels.

When electrification is not possible, the use of green hydrogen should be considered. Finally, careful consideration of the impacts of the supply chain and the use of sustainably sourced biomass can further help companies to lessen their carbon footprint.

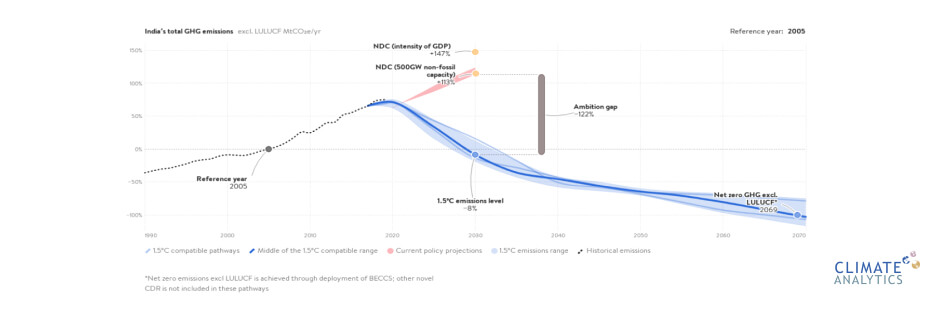

India’s booming economy has caused national emissions to rise from 291 million tonnes in 1980 to 2.7 billion tonnes in 2021. The strength with which the country has established itself among the world's economic powers is also reflected in the portion of global emissions it represents, currently equal to 7%.

A 1.5°C compatible pathway would require India’s share of non-fossil power generation to reach 70-79% by 2030, much higher than the 50% specified in India’s conditional target. Pathways compatible with carbon neutrality also include rapid electrification of the building and the transport sector and, even more importantly, of the national industry.

Industry is the most energy consuming sector in India. Primary energy demand in the sector is heavily dominated by fossil fuels, with a 58% share in 2020.

For India to be aligned with 1.5°C pathways, companies need to prioritize electrification, to reach a share of 30-31% by 2030 and 46-71% by 2050, from 19% of 2019. A sharp decrease in emissions can only be achieved with a strong increase in renewable generation capacity, which would allow to quickly replace coal-generated energy.

Finally, businesses should keep pursuing investments in energy efficiency, which, thanks to the “Perform, Achieve and Trade” (PAT) Mechanism have resulted in savings of approximately 92 Million tonnes of CO₂ between 2012 and 2019.

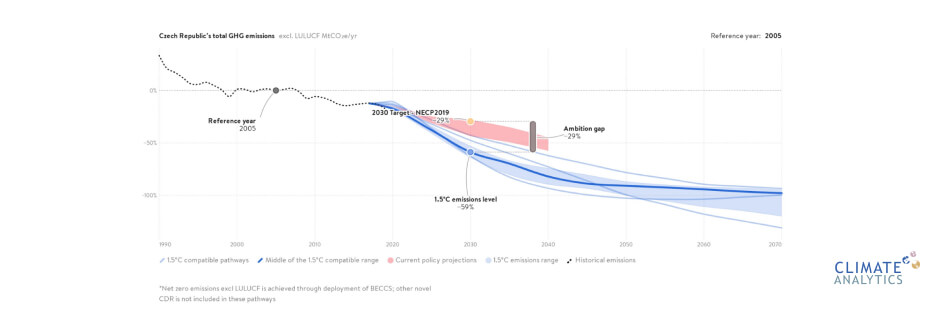

Despite its overall annual emissions being contained due to its limited population, Czech Republic displays some of the highest per capita emissions of the whole EU. This is mainly due to the prominent role of coal in the country’s energy mix, an energy source that would need to be phased out by 2029 if the country was to comply with the Paris agreement.

Czechia is currently aiming for a 17% share of renewables in the power sector by 2030, meaning its ambition is significantly short of what it is needed to be 1.5°C compatible.

To bring industrial emissions down to zero, Czech companies would have to channel capital towards electrification and renewable generation sources, mainly solar and wind.

Further emission savings could come from replacing coal-generated energy with the use of sustainably sourced biomass and from improving on energy efficiency.

As a careful reader would have already understood, nations cannot succeed in the tackling down carbon emissions without the help of private businesses. Companies of every size today share important responsibilities with customers and governments, having therefore to strive for something more than just profit. However, as observed earlier, the forerunners will not only do a favour to the planet, but first and foremost to themselves, building a lasting competitive advantage, ensuring flexibility within their organizations and staying ahead of the ever-evolving regulatory framework.

If you are interested in measuring, reporting and cutting down your company’s emission do not hesitate to contact our expert for efficient and highly customised solutions.